Napule, Napule

“Il nome, il simplice nome di Napoli è uno dei più carichi di forza imaginativa che siano al mondo[1]”.

From the air, or alternatively from the heights of Castel Sant'Elmo, the view of the gulf's waters confirms Naples' role as a gateway to the Tyrrhenian Sea, always with the unmistakable silhouette of Mount Vesuvius in the background.

The city's origins can be traced back to the early Greek colonization and also to legend. The latter, rooted in mythology, tells of the siren Parthenope, whose name has become synonymous with the city. “Quindi la favola, che Partenope, una di ese, dopo di essere stata vinta da Ulisse, si gettase disperata nel mare, e venisse dai flutti battuta in sulla spiaggia nelle vicinanze di Falèro”. (…) “Sia dai Calcidesi venuti direttamente dall’Eubea, sia da quelli del medesimo Popolo che già prima si erano stabiliti in Cuma, fondosi una città che ebbe il nome di Partenope della Sirena[2]”. And which can also be traced in the Silvae of Publius Papinius Statius: “Iuvenesque Parthenopen, nostro qui tot fastigia monti, tot iurides lucos, tot saxa imitantia vultus aeroque, tot scrito viventes lumine ceras fixisti[3]”. Although, in essence, these are myths not so far removed from reality; this reality is found in the Euboean expeditions to the Western Mediterranean, in the founding of the colony of Pithecusae, on present-day Ischia, which expanded to the mainland at Cumae and the islet of Megaris, and from there to a newly created city, Nea Polis, Naples. Roman and Byzantine city, Lombard duchy, Norman, Swabian, Catalan, and Spanish rule until the arrival of the Bourbons and Italian unification.

These are the antipodes of northern Italy, the antithesis of Milan, Turin, or Trieste. Forcella, Montesanto, La Sanità, the Spanish Quarter, and the street markets are extensions of the atmosphere and spirit of downtown Naples: shouts and gestures, noise and colour, a mix of people working and those simply watching. Goethe, who visited the city in February 1787, wrote in Italienische Reise[4]: “People live their lives in the streets, sitting in the sun whenever it shines. The Neapolitan believe to be in possession of paradise”.

However, Neapolitans have lived periods of great hardship, not reaching the eruptions of Vesuvius; poverty and plague have ravaged the city. Naples suffered two major plague outbreaks in 1837 and 1854, and cholera outbreaks in 1865, 1867, and 1884. During the first, the poet Giacomo Leopardi died; the second claimed more than 7,000 victims; and the 1884 epidemic was well documented in the writings of the Swedish physician Axel Munthe, in his History of San Michele (1932).

The poverty that has almost continuously hit the city is a legacy of the forced overcrowding imposed by the Spanish viceroys, which contributed to the overpopulation of alleyways and basements, facilitating the spread of disease. In 1860, with the unification of Italy, Naples became the most populous city in the new country; with half a million inhabitants, at that time it was surpassed in Europe only by London, Paris, Vienna, and Saint Petersburg. In the 1880s, work began on the so-called Risanamento, a project to decongest the most compact and densely populated areas. The Rettifilo, a wide avenue connecting the railway station to the port, was opened; now is Corso Umberto I. To achieve this, numerous buildings were demolished, and their inhabitants, some 80,000 people, were relocated to already overcrowded areas, obtaining just the opposite of the intended effect. The journalist Matilde Serao described the new avenue as a screen that did nothing but conceal the misery. Serao described some of these urban development projects in her book Il ventre di Napoli (1884). “Sopra tutte le strade che la traversano (sezione Vicaria), una sola è pulita, la via del Duomo: tutte le altre sono rappresentazioni della vecchia Napoli, affogate, brune, con le case puntellate, che cadono per vecchiaia. Vi è un vicolo del Sole, detto così perchè il sole non vi entra mai. (…) In sezione Mercato, niuna strada è pulita; pare che da anni non ci passi mai lo spazzino ; ed è forse la sporcizia di un giorno. (…) Tutto il quartiere della Pignasecca, dal largo della Carità, sino ai Ventaglieri, passando per Montesanto, è ostruito da un mercato continuo. Vi sono le botteghe, ma tutto si vende nella via ; i marciapiedi sono scomparsi[5]”. The Spanish journalist Carmen de Burgos (1867-1932) travelled to Naples for the first time in 1906 with her daughter. His impressions were captured in his book Por Europa (Impresiones) Francia, Italia y Mónaco (Through Europe (Impressions) France, Italy and Monaco), published in 1906: “La miseria del pueblo de Nápoles es incomprensible, cuando se ve esta ciudad tan bella, tendida sobre sus colinas, dulce y perezosa como si arrullase el sueño de la antigua sirena de Partenope[6]”. As a consequence, almost one hundred thousand Neapolitans, a fifth of the population, had already left the city by 1906, primarily for the United States.

In Naples are the tombs of Virgil (alleged) and Leopardi (actual), both located in what is now Virgiliano Park, west of the city. Boccaccio and Petrarch also resided once in Naples. But for a celebrated citizen, there is none like its patron saint, San Gennaro, who, after his martyrdom, was first buried in Agromarciano, near where he was executed, before being moved to the catacombs that are now known by his name, near Capodimonte. Later, his bones were moved to Beneveto and Montevirgine before being transferred to the cathedral's crypt, where they now rest. There, the two glass vials containing his blood are preserved, the blood that liquefies three times a year, to the amazement and certainty of the faithful. The cathedral was built on the site of a former Greek temple dedicated to Apollo and Poseidon. Donatien Alphonse François, the infamous Marquis de Sade, remarked during his visit to the city that "San Gennaro is a Gothic-style church in which I saw nothing noteworthy, except for two rather beautiful Corinthian columns."

From above, whether from the plane taking you to Capodichino Airport or from the walls of Castel Sant'Elmo, the fracture that divides the old town is clearly visible. It is the line formed by the streets of Benedetto Croce, San Biagio dei Librai and Via Vicaria Vecchia, the first decumanus of the city and popularly known as Spaccanapoli —spaccare means to break, to split —. Here you will find a succession of tiny restaurants, shops of any kind, churches, saints on the corners, papers on the ground, painted walls, posters with obituaries, tables that take up space from the sidewalk, motorcycles that drive recklessly, people, lots of people, locals and foreigners, more saints and more churches, arcades that lead to almost hidden inner courtyards, a porticoed section, sweets and more sweets, kiosks, a photograph of the actors Totò e Peppino and anything else imaginable.

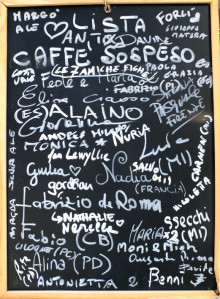

Another popular thoroughfare is Via Toledo, pedestrianized in its lower section, where it ends to the south of the city and opens into the large Piazza del Plebiscito, which commemorates the incorporation of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies into Italy on October 21, 1860. Here you'll find a large arcaded crescent with the neoclassical façade of the Royal Pontifical Basilica of San Francesco di Paola, which imitates the Pantheon in Rome, equestrian statues of Charles of Bourbon and Ferdinand I, and, opposite, the Royal Palace. Turning the corner, you'll come to Piazza Trieste e Trento, where the façade of the Teatro San Carlo appears, one of the first opera houses in Europe; it was inaugurated on the feast day of Saint Charles, November 4, 1737, with a performance of Achilles in Scyros by opera librettist Pietro Metastasio. The theatre shares the square with the famous Caffè Gambrinus, a classic establishment dating back to 1860 that retains its original decor. Gabriele D’Annunzio, Oscar Wilde, Benedetto Croce, Sartre, and the aforementioned journalist Matilde Serao, who founded the newspaper Il Mattino, once had breakfast there. Years later, the newspaper was directed by fellow journalist Giovanni Ansaldo (1895-1969), who wrote about the city. “Ci sono dunque due modi di vedere Napoli. L’uno è quello di conformarsi al quadro tradizionale e convenzionale forgiato dai secoli e dal gusto delle generazioni passata, trascurando la sua realtà presente; e l’altro è quello di dimenticare quel quadro piacente e lusingatore, puntando invece a scoprire la realtà attuale[7]”.

Opposite the theatre is one of the entrances to the Galleria Umberto I, a Belle Époque, fin-de-siècle gallery in the style of those in Paris or Milan, with a large dome fifty-six meters high at the intersection of the passageways. There, on the floor of the crossroads, the signs of the zodiac are represented in mosaic; the one corresponding to Taurus seems to be doing considerably better than its Milanese counterpart, the one whose testicles it seems fashionable to step on by, as if that weren't enough, turning your heel three times. Ansaldo said about the gallery that “è il monumento che rivela con maggiore ingenuità la tentazione, che di tanto in tanto asilla Napoli, di “faré come Milano”. E si badi, che sotto molti aspetti, le gallerie di Napoli è superiore a quella di Milano[8]”.

The equally famous Via Toledo connects this area of the Plebiscito, the Teatro San Carlo, and the Galleria with Piazza Dante. Its southern section is where the main fashion shops are concentrated. Via Toledo is mentioned in the lyrics of Renato Carosone's famous Neapolitan song Tu vuò fà l’americano: “Puorte o cazone cu 'nu stemma arreto / 'na cuppulella cu 'a visiera alzata. / Passe scampanianno pe' Tuleto / camme a 'nu guappo pe' te fa guardà![9]” Above Dante, next to Piazza Cavour and before reaching the Sanità district, is the National Archaeological Museum, where most of the paintings, sculptures and objects extracted from the excavations of Pompeii and Herculaneum have been gathered.

© J.L.Nicolas

[1] “The name, the simple name of Naples, is one of the most imaginatively charged in the world.” Giovanni Ansaldo, Passeggiata Napoletana, 1961.

[2] “Hence the fable that Parthenope, one of the Sirens, after being defeated by Odysseus, threw herself desperately into the sea and was swept away by the waves near Phalerum. (…) Whether by the Chalcidians who came directly from Euboea, or by those of the same people who had already settled in Cumae before, a city was founded which took the name of Parthenope of the Siren.” Bartolomeo Capasso, Napoli e Palepoli, 1989.

[3] "Young Parthenope, who has adorned our mountain with so many buildings, with so many green forests, with so many marble and bronze statues that reproduce faces, with so many paintings animated with plastic life." Publius Papinius Statius, Silvae III 1.92.

[4] Italian Journey.

[5] “Of all the streets that cross it — the Vicaria district —, only one is clean, Via del Duomo; all the others are representations of old Naples, poorly ventilated, dark, with houses propped up and falling down from age. There is an alley of the Sun, so called because the sun never shines there. (…) In the Market area, there isn't a single clean street left. It seems as if the street sweeper hasn't come by for years, but it's just a single day's rubbish. (…) The entire Pignasecca district, from the Carità to the Ventaglieri, passing through Montesanto, is clogged up by a continuous market. There are shops, but everything is sold in the street; the sidewalks have disappeared”. Matilde Serao, Il ventre di Napoli, 1884.

[6] “The misery of the people of Naples is incomprehensible, when one sees this beautiful city, spread out over its hills, sweet and languid as if lulled by the sleep of the ancient siren of Parthenope”.

[7] “There are, therefore, two ways of seeing Naples. One is to be content with the traditional and conventional image shaped by centuries and the tastes of past generations, neglecting its present reality; and the other is to forget that pleasant and flattering image, aspiring, instead, to discover its present reality”. Giovanni Ansaldo, Passeggiata Napoletana, 1961.

[8] “It is the monument that most naively reveals the temptation, which sometimes besets Naples, to 'do as Milan does.' And it should be noted that, in many respects, Naples' galleries are superior to those of Milan.” Giovanni Ansaldo, Passeggiata Napoletana, 1961.

[9] “You wear trousers with a mark on the backside / A cap with the visor turned up / You strut along (Via) Toledo / like a handsome fellow, to get noticed...”.